|

|

| |

Welsh

Slate

Museum

Â

History and Archeology

History

and Archaeology Slate has been quarried in the area for over 1800 years;

the Romans who lived in Segontium (Caernarfon) used slate from local quarries

to build their fort. Hundreds of years later King Edward 1 of England

built a series of castles along the North Wales coast and slate from the

Conwy Valley was used in the castles of Conwy, Beaumaris and Caernarfon.

History

and Archaeology Slate has been quarried in the area for over 1800 years;

the Romans who lived in Segontium (Caernarfon) used slate from local quarries

to build their fort. Hundreds of years later King Edward 1 of England

built a series of castles along the North Wales coast and slate from the

Conwy Valley was used in the castles of Conwy, Beaumaris and Caernarfon.

Although the Romans knew about the value of state as a roofing material, it was not until the end of the eighteenth century that the demand became significant. Then it developed rapidly with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. Roofing slates from Dinorwig and other North Wales quarries were not only shipped all over Britain but also found their way to continental Europe and North America where they were used to meet the expanding housing and factory needs in the industrial cities.

The slate industry in North Wales developed rapidly, and as a result of the expansion, Bethesda and Blaenau Ffestiniog were transformed into active industrial towns. The ports experienced similar rapid growth.

By the 1870�s slate mining had become one of the most important of Welsh industries. Dinorwig was the second largest slate quarry in the world, overtaken only by the neighbouring Penrhyn quarry, which extracts the same Cambrian slate veins. Both Dinorwig and Penrhyn quarry employed over three thousand men. Penrhyn still operates today, kept going by an increase in demand for slate and made profitable by more mechanised ways of working which are also safer and better paid than in the days when Dinorwig still operated.

In 1882 the quarries of Caernarfonshire produced over 280,000 tons of finished roofing slates. Wales produced over four-fifths of the total UK slate. Production reached its peak in 1898 (17,000 men producing 485,000 tons of slate). Transport was also a significant industry with over 3,500 men employed as seamen.

At its peak the Dinorwig slate quarry employed about 3,000 men. Indeed, at the beginning of the 1900s, Dinorwig was one of the largest and most important slate quarries in North Wales. There was even a special rail line that took the slates to Port Dinorwig on the Menai Strait some 8 kilometres west of Bangor. A small stretch of this has been re-opened as the �Llanberis Lake Railway�.

Before

the arrival of modern transport, quarrymen travelled on foot from as far

away as Anglessey each week, crossing the Menai Strait, or walking up

from Caernarfon on a Sunday evening and staying in the quarry barracks

until Saturday lunchtime when they returned to their families and communities

for only 24 hours before starting their return journey to work.

Before

the arrival of modern transport, quarrymen travelled on foot from as far

away as Anglessey each week, crossing the Menai Strait, or walking up

from Caernarfon on a Sunday evening and staying in the quarry barracks

until Saturday lunchtime when they returned to their families and communities

for only 24 hours before starting their return journey to work.

Conditions at the quarry were extremely harsh. Facilities like canteens, places to wash and keep clothes dry were minimal, as were the quarrymen�s wages. Workers had to take a five-year apprenticeship to become a fully-fledged quarryman. It may have been skilled work but it was also dangerous, dirty and unhealthy.

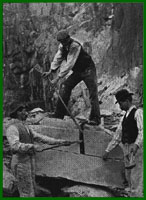

The rockmen had to learn to use explosives and how to handle heavy hammers and chisels - the tools of their trade - whilst dangling on ropes wound round their legs and body to leave their hands free to work at the terraces of slate. Two steel pins inserted into holes at the top of the terraces were the means of fastening the ropes. These men worked in all weathers. Even in the summer conditions were often far from ideal because the frequent rain made the slate slippery and hazardous to stand on.

The quarry covered 324 hectares and was divided into galleries that were 20 to 40 metres deep. The width of the gallery should be three quarters of the depth, although this requirement was rarely applied. The only medical facility was the quarry hospital run by St John Ambulance trained quarrymen who, being volunteers, received no extra pay for this service. Accidents were usually caused by a fall of rock or fragile ropes breaking. The Quarrymen were responsible for all their own ropes, hammers and chisels, which they had to pay for to be sharpened out of their wages.

Even away from the quarry face, in the dressing shed where the slate was split and cut into uniform shapes, there was another hazard - slate dust. The industrial disease, silicosis, the scourge of another industry - coal mining - was also rife at Dinorwig because of the high dust content of the slate mined there.

Quarrymen certainly had a very precarious lifestyle in more ways than one. They were employed only on a monthly contract basis. For the first three weeks they were paid �sub� wages - a bare subsistence payment. In the fourth week the profits and bonus were worked out. Taken out of any bonus payment was the cost of the explosives the quarrymen used, the tools, pneumatic drills; even the air needed to drive this equipment was taken into account in the calculations. It is little wonder then that quarrymen often returned home at the end of the week with little or no bonus.

Knowing how and where to blast the rock meant the difference between profit and loss. The quarrymen had to drill and blast every piece of rock that could be of benefit to them. It was imperative that the production was the very best that could be achieved.

The

slate industry reached its peak towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Then in 1900 came a long and bitter strike which has gone down in history

as the most difficult dispute in welsh industrial life. The quarrymen

at Dinorwig had wanted the North Wales Quarrymen�s Union to represent

them in negotiations over pay and conditions. But after three long years

they failed to achieve this end. Even today, the descendants of the quarrymen

involved in the struggle recall the bitterness felt by the workers at

the time.

The

slate industry reached its peak towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Then in 1900 came a long and bitter strike which has gone down in history

as the most difficult dispute in welsh industrial life. The quarrymen

at Dinorwig had wanted the North Wales Quarrymen�s Union to represent

them in negotiations over pay and conditions. But after three long years

they failed to achieve this end. Even today, the descendants of the quarrymen

involved in the struggle recall the bitterness felt by the workers at

the time.

That strike, in many ways represented a turning point for the state industry. Alternative roofing materials were sought and the demand for slate never again recovered its former level. Today a small market for Welsh slate still exists, and demand in 1983 was stimulated by readily available home improvement grants for renovating the older housing in Britain. At one stage the Welsh industry was unable to meet the needs of the British market and imports were brought in from Spain. By the end of the century its superior qualities of appearance and durability once more made it sought after for many new homes too.

There was a brief resurgence in demand in the 1950s to restore property damaged during the Second World War. Unfortunately, however, by the 1960s demand fell again.

Dinorwig supplied the stone dais upon which Prince Charles sat for his Investiture at Caernarfon Castle, but the day after the quarry�s closure was announced and 300 men were made redundant. So in 1969 the quarry finally stopped production.